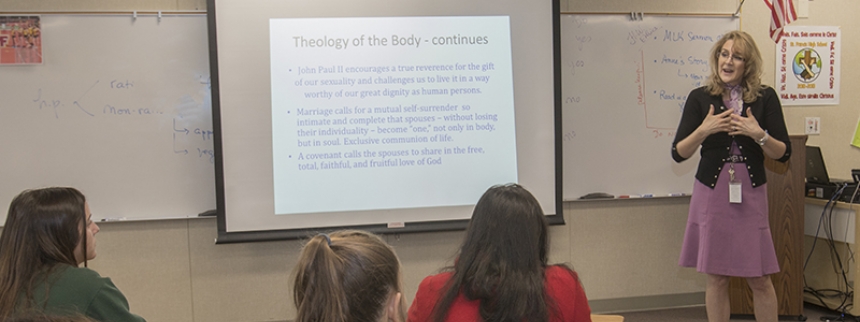

In photo above, Christine L'Hermine-Vlach, a theology teacher at St. Francis Catholic High School in Sacramento, in the classroom with students.

Matters of sex and sexuality bombard teens every day -- coaxing, taunting and persuading them to a point when their brains are saturated with contrary and often confusing messages.

Where, and from whom, will they hear, appreciate and discover the rich meaning and truth of human life? Catholic Herald magazine spoke with high school teachers and a youth minister to get a glimpse of their classrooms, highlighting the important work of listening, loving and forming teens.

Where teens ‘are’ today

“From talking heads on cable news stations to late night talk show hosts, to popular personalities on social media, students are fully immersed in a cacophony of noise,” says Nick Luppino, a theology teacher at Jesuit High School in Carmichael for the past 13 years, 12 of those in the theology department. He laments about the tightly-packaged messages – 15-second sound bites, or 140-character texts.

Technology and instant information at one’s fingertips make some aspects of life abundantly easier but conversely, these techno-extensions of the human body also have whittled away reason in favor of relativism, especially among teenagers.

“This means that only conclusions are ever shared,” Nick says, pointing out that there are no explanations of why one answer is better than another. As a result, the unexplained, often contradictory conclusions lead teens to believe “there is no such thing as a ‘better’ answer,” but rather, it’s simply about personal preference.

“Their experience compels them to a sense that there are no “whys,” Nick concedes, although far from defeated. “In my morality course, we live in the ‘whys’ until a deeper understanding is uncovered.”

“They’re out there getting just one message,” affirms youth minister Andreya Arevalo of St. Mary Parish in Vacaville. She refers to a prevalent “hookup” mindset among teens eager to have a physical or sexual experience because their culture is telling them, “that’s what you do.” She relates a story of a college-aged student happy and excited one day because she planned to “hookup” with someone, and crying the next night, inconsolable about what transpired.

Christine L’Hermine-Vlach, a theology teacher for five years at St. Francis High School in Sacramento who focuses on an ethics course for seniors, concurs. “They want to fit into the world because it’s very hard to be different and separate,” she notes.

Christine recognizes that society tells teens it is OK to discover each other sexually and express themselves with their body. She listens closely to teens who report “science has progressed but the church and religion, in general, are archaic institutions, not growing or moving with the times.” She respects students’ claims of spirituality, but questions if the term is used as a guise to avoid the responsibility of religion.

“Spirituality is some sort of emotion, but religion is an obligation,” Christine says, contrasting how spirituality may be perceived as soothing, while religion immobilizes in the eyes of teens.

Christine sees that students are coming from different places and perspectives, and depending on their origins, Catholic teaching on human sexuality may be met with a range of negative feelings. “It depends on what is discussed at home, if it is discussed at home, the catechetical background of the student and the level of understanding for what it means to have a relationship with God,” she stresses, suggesting an important and necessary spiritual maturity is needed in order to oppose outside pressures.

A better option

Andreya shares that she finds teens “to be hungry for something else,” confiding that most have no idea there is something more: they are hungry for truth and something that “makes sense.”

“They know and feel something is not right” about the common quest to casually encounter the opposite sex, she explains, conveying that this “feeling” is their heart yearning for a better option. They sense an unexplainable disconnect about why it is so intimidating to look someone in the eyes, talk for awhile on the phone, or share a walk holding hands.

Teens want love and they want relationship, but Andreya unfolds how teens cannot connect the dots. They sense a forbidden mystery and fear about sexuality, believing it is dirty or bad. Why then, would you save “it” for someone you love? Yet, they’re also told it offers happiness and joy. It doesn’t add up. They wonder why they feel sad, guilty and alone.

Andreya has been teaching Theology of the Body to teens in her youth ministry for six years. She revels in the vision of teens’ “eyes and minds opening” to the great theological and philosophical work of Saint John Paul II. She describes it as if “light bulbs turn on” as students reach a point over the 10-week course when they acknowledge, “now it makes sense.”

Nick finds that the dilemma he sees is often more about a philosophical deficiency rather than a catechetical deficiency. “They don’t know why church teaching is better than any other,” he says. For this reason, he knows to initiate the dialogue. He does not begin with church doctrine, but rather he weaves an intricate unfolding of the philosophical foundations of Catholic morality before landing on specific doctrine.

“My hope is to hand wonder back to them,” Nick contends with a heartfelt goal. “I want to show them that if they ask, seek and knock with honesty and reverence, creation will reveal the true, good and beautiful, graciously.

“I follow a model set by Saint John Paul II, and help my students recover a more authentic anthropology and epistemology,” Nick adds, describing a method that “allows them to become aware of the inherent meaning in creation and, in particular, the human person.”

Christine, likewise, turns to a toolbox that begins now and journeys back. “I cannot begin with Pope Paul VI’s Humanae Vitae (Of Human Life). I begin with Pope Francis’ Amoris Laetitia,” she says, also embracing Pope Benedict XVI’s Deus Caritas Est, Saint John Paul II’s Theology of the Body, and then, Pope Paul VI’s Humanae Vitae. (Editor’s note: Amoris Laetitia is a post-synodal apostolic exhortation by Pope Francis addressing the pastoral care of families, released on April 8, 2016.)

“I have to start with ‘who are we?’” Christine says, taking students on a journey through psychological and faith development, studying Aristotle to Thomas Aquinas, ultimately encouraging their “openness to grace.”

Christine refers to Pope Francis and how he emphasizes “we need to have a responsible and generous effort to present reason and motivations to choose family and marriage.” She also marvels at the continuity of the popes’ encyclicals and exhortations and how each furthers the ability to grasp the real meaning and content of the teachings on love and human sexuality. She describes them as a beautiful “framework” for the gentle discovery of God’s truth.

Inform and transform

Throughout the weeks of classroom learning, dialogue inevitably circles to the reality of teen culture and its “hookup” nature. Intrigue surfaces on the topic of dating, which isn’t really dating because students often have no idea how to date, spend time with someone, or encounter a person for the purpose of getting to know them – quite possibly another side effect, or result, of technology, the teachers note.

“Teens are invited out in a text or they break up in a text,” Christine says, revealing a miserable dissatisfaction and loneliness among teens who hunger for real “heart-to-heart” relationship but have no idea how to make it happen.

“We long to be loved and to love,” Christine adds, “but it takes awhile to realize we are only truly satisfied with God.” She tells her students that, in fact, their bodies “tell the story of God,” and their biological and theological being is God’s gift to them, inviting them to authentic love and communion.

Andreya suggests to her students that their teenage years should be a time to “focus on you and figure out you.” She advises them to be with friends and go out in groups, learning how to give of themselves in other ways to fully understand meaningful self-giving. “The desires are strong,” she says, noting she encourages students to “redirect” sexual desires and consider self-giving for the good of others in service, or simply by spending time with others.

She demonstrates the concept of “self gift” vividly with an apple cut into many slices. She gives everyone a slice, or a “piece” of the whole, while stressing to students the beauty of a total self gift for a spouse someday. It becomes impossible if pieces of oneself have been given away freely. What’s left for the spouse? Only the discarded core.

“What does your ‘yes’ really mean?” she challenges, asking students to consider if they cannot say “no” now, will they be able to say “no” later?

Andreya clarifies that the message isn’t about restrictions and consequences but rather, that better option they yearn for within their hearts. “They already know this,” she notes with certainty. “It is stamped on the heart,” she says, recalling the words of author Christopher West, who shared John Paul II’s Theology of the Body widely, giving new voice and language to church teaching on love and sexuality.

The message empowers them and helps teens to know “who you are, who you’re meant to be, and who you can be,” Andreya says with conviction, confident when students say, “I actually want to be that person.”